Table of Contents

In a world obsessed with data, deliberation, and extensive analysis, Malcolm Gladwell‘s “Blink: The Power of Thinking Without Thinking” presents a counterintuitive and compelling argument: sometimes our best decisions happen in the blink of an eye. Published in 2005, this groundbreaking work challenges conventional wisdom about decision-making and offers profound insights for leaders, entrepreneurs, and anyone seeking to understand the hidden forces that shape our choices.

Gladwell, a staff writer for The New Yorker and author of the phenomenal bestseller “The Tipping Point,” brings his signature blend of engaging storytelling, scientific research, and cultural analysis to explore the mysterious world of rapid cognition. Through fascinating case studies ranging from art authentication to police shootings, from marriage counseling to military strategy, Gladwell reveals how our unconscious mind processes vast amounts of information in mere seconds, often arriving at conclusions that rival or exceed those reached through months of careful analysis.

For leaders and entrepreneurs navigating today’s fast-paced business environment, this book offers invaluable lessons. In an era where markets shift rapidly, competitive advantages are fleeting, and information overload threatens to paralyze decision-making, understanding the mechanics of snap judgments becomes not just interesting but essential. Whether you’re evaluating a potential hire in minutes, sizing up a business opportunity, reading a room full of investors, or making strategic pivots under pressure, the ability to harness your adaptive unconscious can mean the difference between breakthrough success and missed opportunity.

The Revolutionary Premise: Thinking Without Thinking

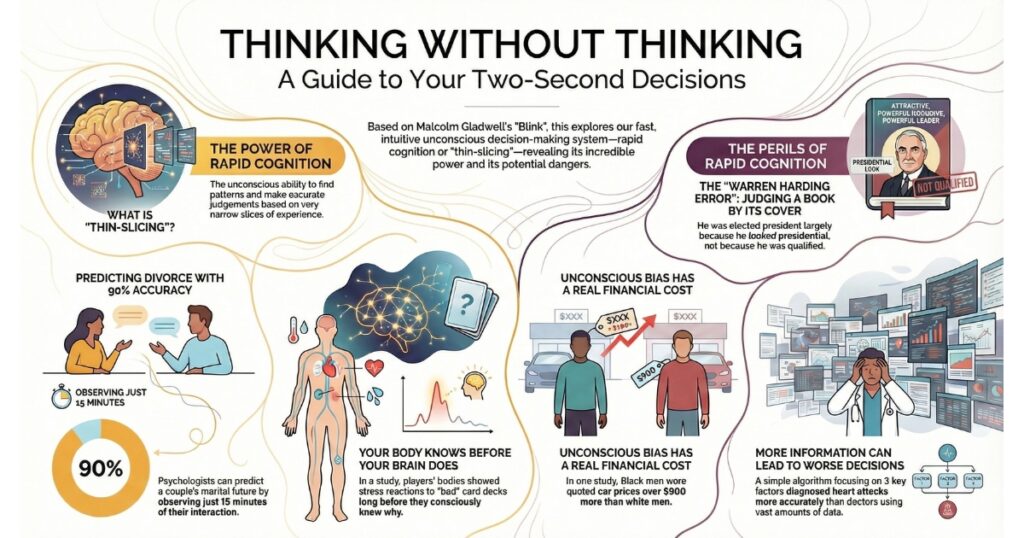

At the heart of “Blink” lies a deceptively simple yet profound insight: the part of our brain that leaps to conclusions operates with remarkable speed and accuracy, often outperforming our deliberate, conscious thinking. Gladwell calls this rapid cognition “thin-slicing,” which he defines as the ability of our unconscious to find patterns in situations and behavior based on very narrow slices of experience.

The book opens with a captivating story about the J. Paul Getty Museum’s purchase of an ancient Greek statue called a kouros. The museum spent fourteen months conducting scientific tests, examining documentation, and performing detailed analysis to authenticate the piece. Every test suggested it was genuine. Yet when several art experts first laid eyes on the statue, they experienced immediate, intuitive doubts. One said he felt “intuitive repulsion.” Another noticed something wrong with the fingernails but couldn’t articulate why. These experts, in those first two seconds, detected what fourteen months of scientific analysis missed: the kouros was likely a fake.

This story exemplifies Gladwell’s central argument: our unconscious mind operates as a kind of giant computer that quickly and quietly processes enormous amounts of data we need to function effectively. This isn’t the dark, murky unconscious described by Freud, filled with repressed desires and hidden motivations. Rather, it’s what psychologist Timothy Wilson calls the “adaptive unconscious,” a sophisticated mental system that has evolved to help us survive and thrive by making lightning-fast assessments of our environment.

The Science Behind Snap Judgments

Gladwell supports his thesis with compelling research from psychology, neuroscience, and behavioral economics. One particularly striking example comes from the University of Iowa, where researchers created a gambling game with four decks of cards. Two red decks and two blue decks. Unbeknownst to participants, the red decks were rigged with high rewards but devastating losses, while the blue decks offered steady, modest gains. The winning strategy was to avoid the red decks entirely.

What the researchers discovered was extraordinary: after turning over about fifty cards, most participants developed a hunch that the blue decks were better, though they couldn’t explain why. After eighty cards, they could articulate the game’s structure and explain their preference rationally. But here’s the remarkable part: their bodies knew the truth much earlier. Stress detectors measuring their palm sweat showed participants began generating stress responses to the red decks by the tenth card, forty cards before they consciously knew something was wrong. Even more impressive, they began adjusting their behavior around the same time, favoring blue cards before they could explain why.

This experiment reveals a fundamental truth about human cognition: we have two decision-making systems. The first is conscious, logical, and deliberate. It takes its time, weighs evidence carefully, and eventually arrives at conclusions we can articulate and defend. The second system operates much faster. It starts working almost immediately, picks up patterns rapidly, and reaches conclusions without immediately telling us how it reached them. These conclusions manifest as feelings, hunches, and intuitions that often precede our ability to explain them.

The Marriage Laboratory: Predicting Divorce in Fifteen Minutes

One of the most compelling demonstrations of thin-slicing comes from psychologist John Gottman’s research on marriage. Over decades, Gottman brought more than three thousand married couples into his laboratory at the University of Washington. He developed an elaborate coding system called SPAFF (specific affect) with twenty separate categories for every conceivable emotion a married couple might express during conversation.

Gottman’s method was meticulous: he videotaped couples discussing contentious topics from their marriage, then analyzed every second of interaction, assigning codes to each emotional expression. He tracked facial expressions, body language, heart rates, temperature changes, and even how much partners fidgeted in their seats. All this data was fed into complex equations.

The results were stunning. If Gottman analyzed an hour of a husband and wife talking, he could predict with ninety-five percent accuracy whether that couple would still be married fifteen years later. With just fifteen minutes of observation, his success rate remained around ninety percent. Most remarkably, his colleagues discovered that even three minutes of observation yielded fairly impressive accuracy in predicting divorce.

What was Gottman detecting? He discovered that marriages have distinctive signatures, patterns that emerge consistently regardless of what specific topic the couple discusses. The most critical factor he identified was the ratio of positive to negative emotion: for a marriage to survive, couples need at least five positive interactions for every negative one. Even more significant was his identification of what he called the “Four Horsemen” of relationship apocalypse: defensiveness, stonewalling, criticism, and especially contempt. Contempt, Gottman found, was so toxic that its presence alone could predict divorce and even affect the physical health of partners, compromising immune system function.

The marriage research demonstrates a crucial principle for leaders and entrepreneurs: complex outcomes often have identifiable patterns that can be detected quickly when you know what to look for. Just as Gottman doesn’t need to know everything about a couple’s history, finances, or circumstances to predict their future, leaders don’t always need exhaustive data to make accurate assessments.

The Dark Side of Rapid Cognition: The Warren Harding Error

Gladwell doesn’t present snap judgments as infallible. The book’s third chapter, titled “The Warren Harding Error,” explores how rapid cognition can lead us catastrophically astray. Warren Harding, who became the twenty-ninth President of the United States, was by most historical accounts one of the worst presidents in American history. Yet he was elected largely because he looked presidential. Standing nearly six feet tall with a distinguished appearance, silver hair, and commanding presence, Harding made an overwhelming first impression that caused people to leap to unwarranted conclusions about his character, intelligence, and leadership ability.

This phenomenon of being seduced by surface characteristics demonstrates what happens when our unconscious picks up on the wrong cues. Gladwell explores this through research on implicit associations, introducing readers to the Implicit Association Test developed by psychologists Anthony Greenwald, Mahzarin Banaji, and Brian Nosek. This test reveals unconscious biases we may not even know we possess.

The IAT works by measuring how quickly we make associations between concepts. For instance, when asked to categorize words and faces, most people respond faster when asked to pair European American faces with positive words and African American faces with negative words than when the associations are reversed. More than eighty percent of test-takers show this pro-white bias, even many African Americans themselves. This doesn’t mean people are consciously racist; rather, it reveals how our unconscious absorbs cultural messages and forms associations we may consciously reject.

These implicit associations have real consequences. In a remarkable study conducted in Chicago, researchers sent thirty-eight people of different races and genders to car dealerships with identical scripts and backgrounds. The white men received initial price quotes averaging seven hundred twenty-five dollars above the dealer’s cost. White women were quoted nine hundred thirty-five dollars above cost. Black women received quotes of one thousand one hundred ninety-five dollars above cost. Black men were quoted one thousand six hundred eighty-seven dollars above invoice, and even after forty minutes of bargaining, still paid nearly eight hundred dollars more than white men who hadn’t negotiated at all.

For leaders and entrepreneurs, the Warren Harding Error serves as a crucial warning: our snap judgments can be corrupted by irrelevant factors like height, attractiveness, race, or gender. Gladwell demonstrates this with CEO data showing that while the average American man is five foot nine, the average male CEO is just under six feet tall. Among Fortune 500 CEOs, fifty-eight percent are six feet or taller, compared to just fourteen and a half percent of the general population. We unconsciously associate physical stature with leadership ability, often to our detriment.

Creating Structure for Spontaneity: Lessons from War Games

One of the book’s most dramatic stories involves a massive military simulation called Millennium Challenge ’02, which cost a quarter billion dollars and was designed to test new Pentagon theories about network-centric warfare. The simulation pitted a well-resourced “Blue Team” representing the United States against a “Red Team” commanded by retired Marine Corps Lieutenant General Paul Van Riper.

Blue Team had everything: sophisticated computer models, real-time battlefield information, extensive intelligence, and methodologies for systematically understanding adversary systems. Red Team, by contrast, was supposed to represent a rogue commander in the Persian Gulf with limited resources. The Pentagon expected Blue Team to dominate through superior information and technology.

Instead, Van Riper’s Red Team destroyed Blue Team in the opening hours. How? Van Riper understood that in fast-moving, high-stress combat situations, elaborate decision-making systems become liabilities rather than assets. While Blue Team held meetings and analyzed data matrices, Van Riper empowered his commanders to make rapid decisions based on experience and intuition. He communicated through motorcycle couriers instead of electronic channels that could be monitored. He launched a surprise attack using unconventional tactics, and in minutes, had sunk sixteen American ships.

The Millennium Challenge story reveals a paradox: spontaneity requires structure. Van Riper didn’t simply act randomly or impulsively. His success came from creating an environment where rapid cognition could flourish. He established clear intent and guidance, then trusted his subordinates to execute without constant oversight. He recognized that in moments of crisis, forcing people to explain and justify their instincts destroys the very capabilities that make those instincts valuable.

Gladwell contrasts this with research on improvisation comedy, which appears spontaneous but operates according to strict rules. The most important rule is “agreement”: improvisers must accept whatever their partners introduce rather than blocking or denying it. This simple structure paradoxically enables greater creativity and spontaneity than trying to plan everything in advance. Leaders can learn from this: the key isn’t eliminating structure but creating the right structures that enhance rather than impair rapid cognition.

When Too Much Information Hurts: The Emergency Room Revolution

Perhaps nowhere is the tension between analysis and intuition more critical than in medicine, where misdiagnosis can mean death. Gladwell explores this through the story of Cook County Hospital in Chicago and cardiologist Lee Goldman’s revolutionary algorithm for diagnosing heart attacks.

Traditionally, emergency room doctors faced with chest pain patients gathered enormous amounts of information: patient history, risk factors like smoking and obesity, detailed symptoms, family history, stress levels, and more. They ran extensive tests and made complex judgments weighing dozens of variables. The problem was their accuracy was terrible. When presented with twenty identical case histories, doctors’ diagnoses ranged from zero to one hundred percent probability of heart attack for the same patients. They were essentially guessing.

Goldman took a radically different approach. Through mathematical analysis of hundreds of cases, he identified just a few critical factors: the evidence from the electrocardiogram combined with three urgent risk indicators (unstable angina, fluid in the lungs, and low blood pressure). By focusing exclusively on these variables and ignoring everything else, Goldman’s algorithm dramatically outperformed physician judgment. It was seventy percent better at recognizing patients who weren’t having heart attacks, and it correctly identified serious cases ninety-five percent of the time compared to seventy-five to eighty-nine percent for experienced doctors.

The lesson is profound: more information doesn’t always improve decisions. Often it introduces noise and confusion that overwhelms our ability to detect the underlying signal. Goldman’s algorithm worked because it edited ruthlessly, focusing only on what truly mattered. This challenges a fundamental assumption in business and life: that gathering more data, conducting more analysis, and considering more factors leads to better outcomes.

Gladwell extends this principle through the concept of “verbal overshadowing,” research showing that forcing people to explain their judgments can actually impair accuracy. In one study, people shown faces for just seconds could later identify those faces from a lineup reasonably well. But if asked to write detailed descriptions of the faces first, their recognition accuracy plummeted. The act of translating visual memory into words disrupted their unconscious facial recognition abilities.

The Perils of Market Research: Why Experts See What Others Miss

Gladwell’s exploration of market research challenges another business sacred cow: the reliability of asking consumers what they want. He illustrates this through the fascinating story of Kenna, a talented musician who was loved by industry insiders but performed dismally in market testing. When Kenna’s music was played for focus groups and rated by thousands of consumers, the results were unequivocal: people didn’t like it. Rating services predicted his music had “limited potential to gain significant radio airplay.”

Yet everyone who truly understood music loved Kenna. Craig Kallman, co-president of Atlantic Records, was “blown away” after hearing Kenna’s demo. Fred Durst of Limp Bizkit heard one song over the phone and said “Sign him!” MTV played his video four hundred seventy-five times. His live performances attracted devoted crowds. How could the experts be so right while the market research was so wrong?

Gladwell’s explanation centers on the difference between expert and novice first impressions. The problem with most market research is that it asks people without expertise to make judgments about things they don’t understand. This is like the famous Pepsi Challenge, where Pepsi consistently beat Coke in blind taste tests despite Coke’s market dominance. The issue? Sip tests measure a different phenomenon than actual consumption. Pepsi’s sweeter taste and citrus burst provide an advantage in small sips but can become cloying over an entire can. People’s first impression from a sip doesn’t predict their experience of drinking the whole beverage.

Even more problematic, asking people to explain their preferences can corrupt those preferences. In one study, people who tasted strawberry jams without explanation ranked them similarly to expert ratings. But when asked to write explanations for their preferences first, their rankings became essentially random, no longer correlating with expert assessments. The act of analyzing destroyed their natural ability to judge quality.

The solution isn’t to ignore consumer input but to recognize the limits of explicit feedback, especially for novel products or experiences. Experts develop sophisticated vocabularies and frameworks that allow them to accurately articulate their rapid cognitions. Professional food tasters, for instance, use detailed rating scales across dozens of specific attributes. They’ve psychoanalyzed their taste responses the way psychotherapy patients analyze their emotions. This training allows them to translate unconscious reactions into reliable conscious assessments.

The Tragedy of Amadou Diallo: When Mind-Reading Fails

The book’s most sobering chapter examines the 1999 shooting of Amadou Diallo, an unarmed twenty-two-year-old immigrant from Guinea who was killed by four New York City police officers who fired forty-one bullets at him in a dark Bronx vestibule. The officers mistook his wallet for a gun. How could trained professionals make such a catastrophic error in judgment?

Gladwell’s analysis introduces the concept of “mind-reading,” our natural ability to interpret others’ intentions and emotional states from facial expressions and behavior. Normally, we excel at this. We can distinguish someone who is suspicious from someone who is merely curious, someone who is brazen from someone who is terrified, someone who is dangerous from someone who is afraid. Research by psychologist Paul Ekman has identified specific facial action units corresponding to every human emotion, and these expressions appear universally across cultures.

The Diallo shooting represents a complete breakdown in mind-reading, and Gladwell identifies why: extreme stress combined with insufficient time. When heart rates exceed one hundred seventy-five beats per minute, cognitive processing begins to shut down. Vision narrows dramatically. Sound becomes distorted or disappears entirely. Fine motor control deteriorates. The body enters a survival mode that sacrifices higher reasoning for primitive fight-or-flight responses. Police officers who have shot suspects in combat describe seeing individual bullets hit their targets, experiencing time in slow motion, and hearing nothing despite their guns firing repeatedly.

Under this extreme arousal, the officers couldn’t read Diallo’s face or behavior accurately. They saw a young black man in a high-crime neighborhood late at night. When he reached for his pocket, their heightened state of arousal and unconscious associations transformed a wallet into a gun. The first mistake triggered a cascade: once the shooting started, each officer interpreted the others’ gunfire as evidence that Diallo was armed and shooting back.

The lesson for leaders is that rapid cognition, while powerful, operates within constraints. Time pressure and stress can push us into a form of temporary autism where we lose our ability to read social situations accurately. We construct rigid systems to explain ambiguous information, and we become unable to update those interpretations as new information arrives. The solution isn’t to eliminate snap judgments but to structure situations that keep stress levels within the optimal range where rapid cognition enhances rather than impairs performance.

Practical Lessons for Leaders and Entrepreneurs

The insights from “Blink” translate into specific actionable principles for anyone in leadership or entrepreneurial roles:

- Trust educated intuition, but know its limits. Your unconscious can process vast amounts of information instantly and arrive at accurate conclusions. However, this ability works best when you have genuine expertise in the domain. If you’re hiring for a role you understand deeply, your gut reaction to candidates may be remarkably accurate. If you’re entering an unfamiliar market, your intuitions are more likely to be corrupted by irrelevant factors or stereotypes. Build expertise before trusting your snap judgments.

- Create conditions for good snap judgments. The quality of rapid cognition depends heavily on the environment. When orchestras placed screens between musicians and audition panels, eliminating visual information, they suddenly began hiring far more qualified players, including many women who had previously been excluded. The simple change of context improved decision quality dramatically. Ask yourself: what is your equivalent of the audition screen? How can you structure hiring, strategic planning, or product evaluation to eliminate distracting or biasing factors?

- Recognize that more information isn’t always better. Like the emergency room doctors who performed worse when considering more patient data, we often degrade our decision quality by drowning in details. Identify the critical few variables that truly predict success in your domain, then have the discipline to ignore everything else. This requires courage because it feels irresponsible to discard information. But cluttered thinking produces cluttered results.

- Slow down high-stakes moments. The Diallo shooting demonstrates what happens when time pressure combines with stress. While many business decisions must be made quickly, the highest-stakes choices benefit from building in brief pauses. This doesn’t mean endless deliberation. It means ensuring you have enough time for your adaptive unconscious to process information rather than simply reacting to the first thing you notice. Police departments that banned high-speed chases dramatically reduced both accidents and excessive force incidents because eliminating the chase created space for better judgment.

- Beware of the Warren Harding Error in yourself and others. We all make snap judgments based on irrelevant factors like height, attractiveness, confidence, or similarity to ourselves. The solution isn’t to eliminate rapid assessment but to implement checks against bias. Structured interviews with predetermined questions work better than free-flowing conversations. Blind resume reviews reduce gender and racial bias. Diverse hiring panels catch biases that homogeneous groups miss. These structures don’t eliminate intuition; they create space for better intuition by removing corrupting signals.

- Distinguish between insight problems and analysis problems. Some challenges require systematic, methodical thinking. Others require sudden insight that emerges from unconscious pattern recognition. Forcing analytical frameworks onto insight problems often makes them unsolvable, like the rope-swinging puzzle where explaining your reasoning prevented people from finding the solution. Train yourself to recognize which type of problem you face. For insight problems, immerse yourself in context, then step back and let your unconscious work.

- Practice the skill of thin-slicing in your domain. Rapid cognition improves with deliberate practice, just like any other skill. Paul Ekman can teach people to recognize micro-expressions in thirty-five minutes of training. Wine experts develop sophisticated palates through systematic exposure and vocabulary development. Whatever your field, you can accelerate your ability to make accurate snap judgments by studying examples systematically, developing frameworks for categorization, and getting rapid feedback on your assessments.

- Don’t force explanations prematurely. When you have a strong intuition about something, the impulse to justify it immediately can corrupt that intuition. The act of verbal explanation activates different brain regions than those involved in rapid cognition, and the two can interfere with each other. Instead, act on the intuition first if possible, then analyze why it was right or wrong afterward. This builds your intuitive capabilities rather than short-circuiting them.

- Use market research appropriately. Consumer feedback works best for incremental improvements to familiar products. It fails dramatically for genuinely novel offerings that require expertise to appreciate. The Aeron chair initially tested as ugly because consumers had no context for understanding it. Two years later, it was widely recognized as beautiful. If you’re creating something truly innovative, weight expert opinion more heavily than mass market testing. Better yet, observe behavior rather than asking for opinions.

- Build margin for error into high-pressure decisions. Military strategists talk about “white space,” the distance between you and potential threats that creates time for assessment. In business, white space might mean cash reserves that let you avoid desperate decisions, longer hiring timelines that prevent settling for mediocre candidates, or relationships with multiple suppliers that reduce panic when one fails. This margin allows your rapid cognition to function optimally rather than being overwhelmed by urgency.

Conclusion: The Power and Promise of the Two-Second Window

“Blink” ultimately delivers an optimistic message: we have far more capability for good decision-making than we typically recognize, but accessing that capability requires understanding and managing the conditions under which our unconscious operates. The two seconds in which we form first impressions aren’t mysterious or magical. They represent sophisticated information processing that can be studied, understood, and improved.

For leaders and entrepreneurs, this offers both opportunity and responsibility. The opportunity lies in recognizing that you don’t always need months of market research, exhaustive analysis, or complex decision frameworks. Sometimes the answer is right there in front of you, visible in a blink if you’ve trained yourself to see it. The responsibility comes in acknowledging that this powerful capability can be corrupted by bias, distorted by stress, and misapplied to situations where it doesn’t belong.

The most successful leaders aren’t those who trust their gut unquestioningly or those who trust only data and analysis. They’re the ones who understand when to use which mode of thinking, who create structures that enable rather than impair rapid cognition, and who remain humble about the limitations of both approaches. They practice the delicate art of listening with their eyes, as Gladwell puts it in his conclusion about orchestra auditions, learning to distinguish the signal of genuine quality from the noise of irrelevant characteristics.

In our hyperconnected, information-saturated world, the lessons of “Blink” become increasingly relevant. We face more decisions than ever before, with less time to make them. Understanding the science and art of rapid cognition isn’t a luxury for leaders; it’s a necessity. Those who master it gain a powerful competitive advantage: the ability to act decisively when others hesitate, to see patterns others miss, and to navigate complexity with a combination of analysis and intuition that neither approach alone could match.

Malcolm Gladwell’s “Blink” doesn’t offer simple formulas or easy answers. Instead, it provides something more valuable: a framework for understanding one of the most powerful and least understood aspects of human capability. Whether you’re building a startup, leading a team, or simply trying to make better choices in your own life, the insights in this book can transform how you think about thinking itself. And that transformation, more than any specific technique or tactic, may be the ultimate competitive advantage in an uncertain world.